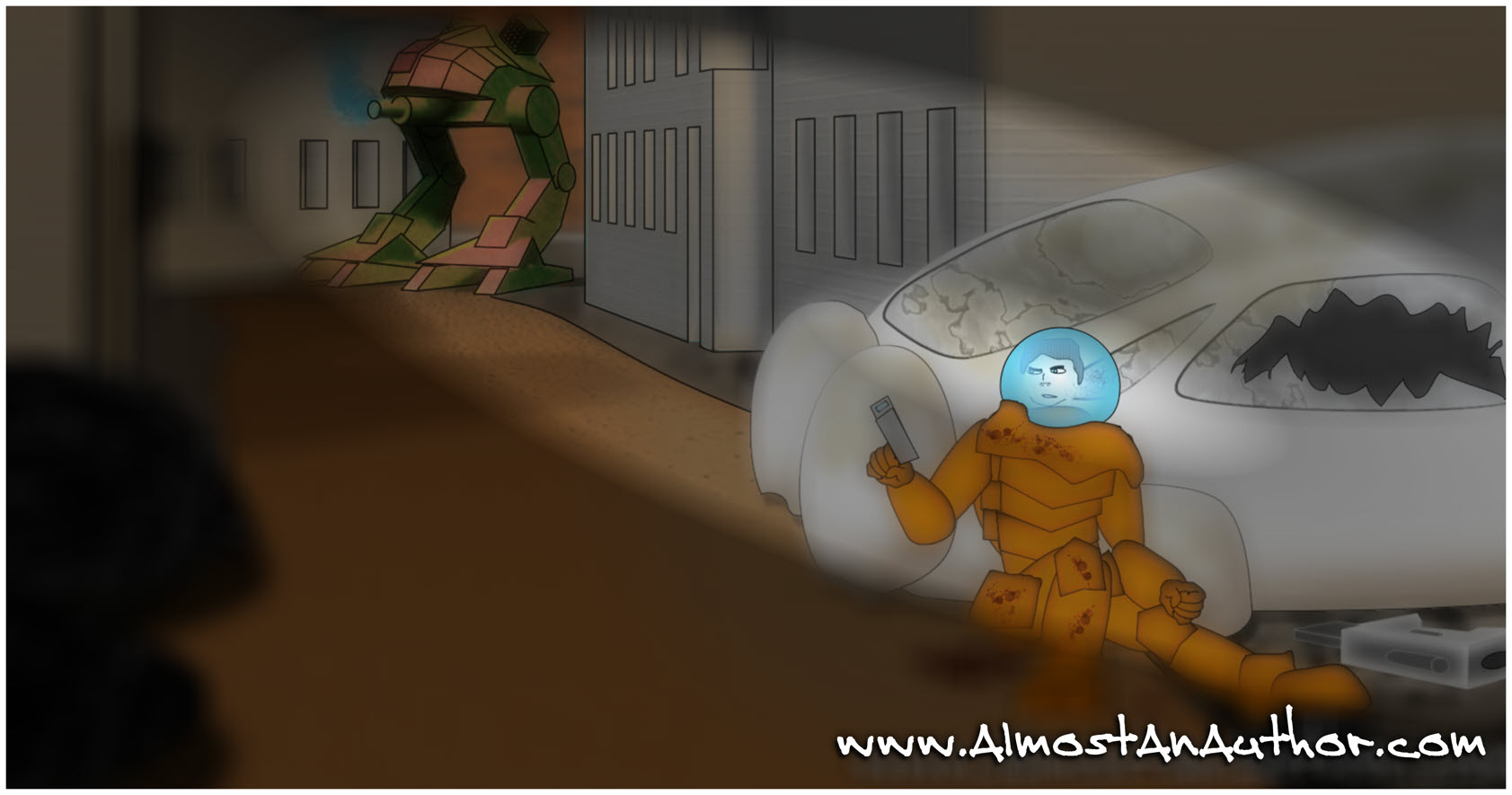

Jim always thought first contact with an alien race would involve ceremony and formality. But standing over the bullet-riddled corpse of one of the gray-skinned creatures, he was just glad thing couldn’t move anymore. He put those romantic ideas out of his head as he holstered his pistol and bent down to examine the invader. Ugly critter. Its colorless skin was covered in scales and three pale struts were melded around each of its limbs. No wait … Jim prodded an exit wound. Those weren’t reinforced supports. Those were the creature’s bones. Exoskeletal bones. Weird.

This month I kick off my series about alien anatomy. We’ll cover some fantastic ways your creatures can move, gain and use energy, reproduce, think and feel, and keep themselves safe from diseases and injury.

Endoskeletons

First we’ll look at the way we move. Humans can manipulate objects, traverse distances, and even make subtle gestures using our musculoskeletal system. Essentially, we have a bone structure under our skin that provides support and a muscle system attached to it that enables articulation. Since this is the structure we personally possess, I won’t spend much time on it. Suffice to say that reptiles, birds, fish, mammals, and more all fit into this category.

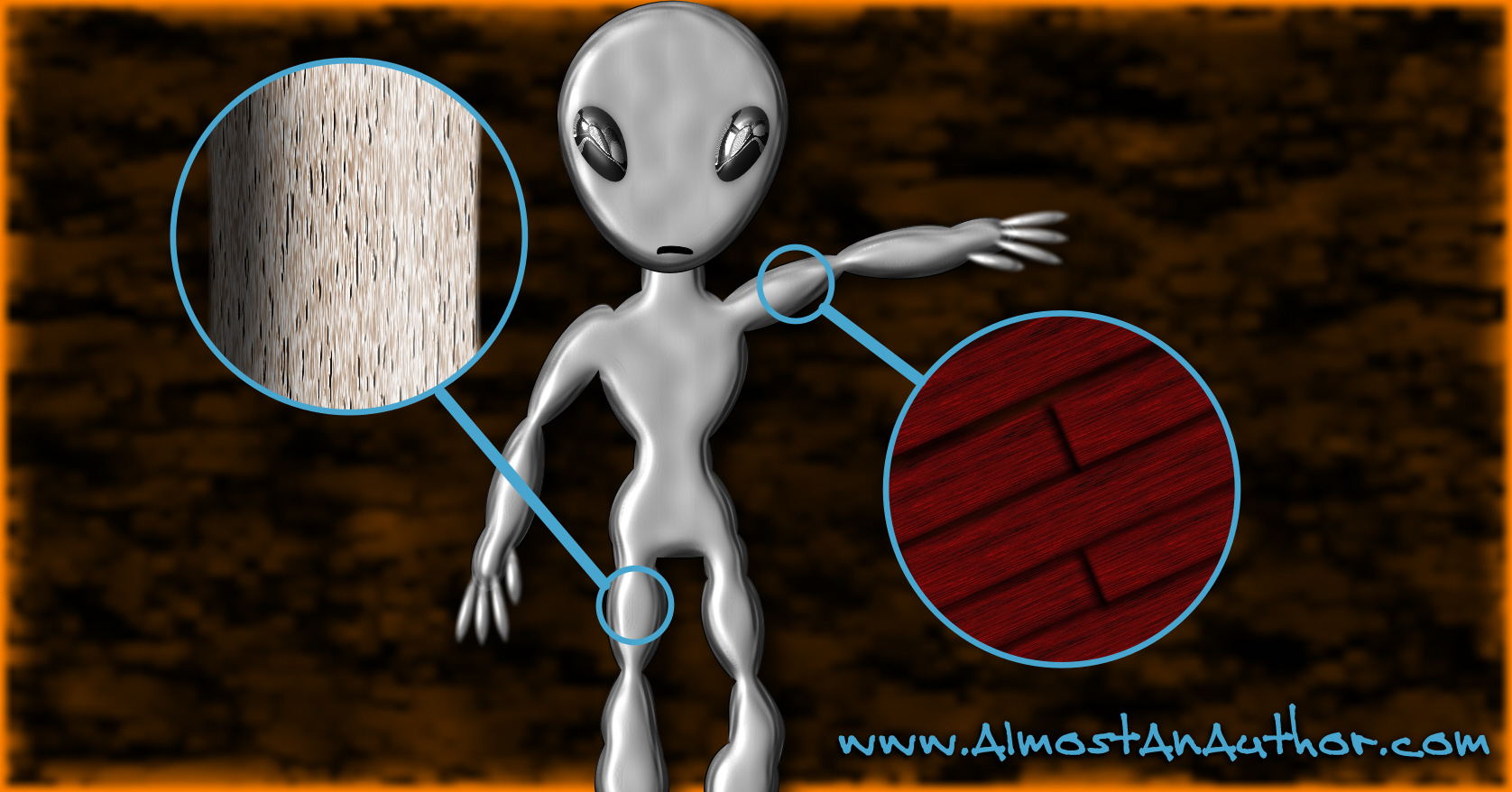

Exoskeletons

But that’s not the only way to make things move. Arthropods have an exoskeleton, meaning the bones form a sort of armor on the outside of the insect and the muscles are connected internally. This may sound really cool, but there are some drawbacks. Armor is relatively heavy and thus exoskeleton-bearing creatures on our planet tend not to grow larger than a couple of feet, unless they live underwater. Movement is also restricted in a fashion similar to medieval plate mail. For example, the grasshopper only has seven joints on each of its legs. Yes, these allow it to make long jumps and simple walking motions, but that is essentially all the grasshopper can do with them.

Exoskeletons also need to be replaced periodically as the organism outgrows its armor. A young and quickly growing creature will “molt” its exoskeleton every few weeks until it reaches an adult size. Even then, molting is done at least annually.

A fantastic creature with an exoskeleton could get around the weight restriction by either living on a low-gravity planet, or using armor segments that are unusually light relative to earth-based arthropods. And while earth-based arthropods may have severe mobility restrictions, an alien creature may have a more sophisticated joint structure. Be creative, and I’m sure you can come up with a way to plague your storyworld inhabitants with zerg clones or similar alien threats.

Hydrostatic Skeletons

Jellyfish may seem like boring critters in the aquarium, but their physiology is fascinating. Gelatinous mass fills a cavity between two layers of single-cell tissue, and this jelly gives the creature its shape and support. This is why they are said to have “hydrostatic” skeletons, because they have a “water support” skeleton structure.

Jellyfish mostly just float around, but when they need to move, they contract a ring of muscles around the edge of its bottom. This expulses water from the mouth region and pushes the jellyfish along.

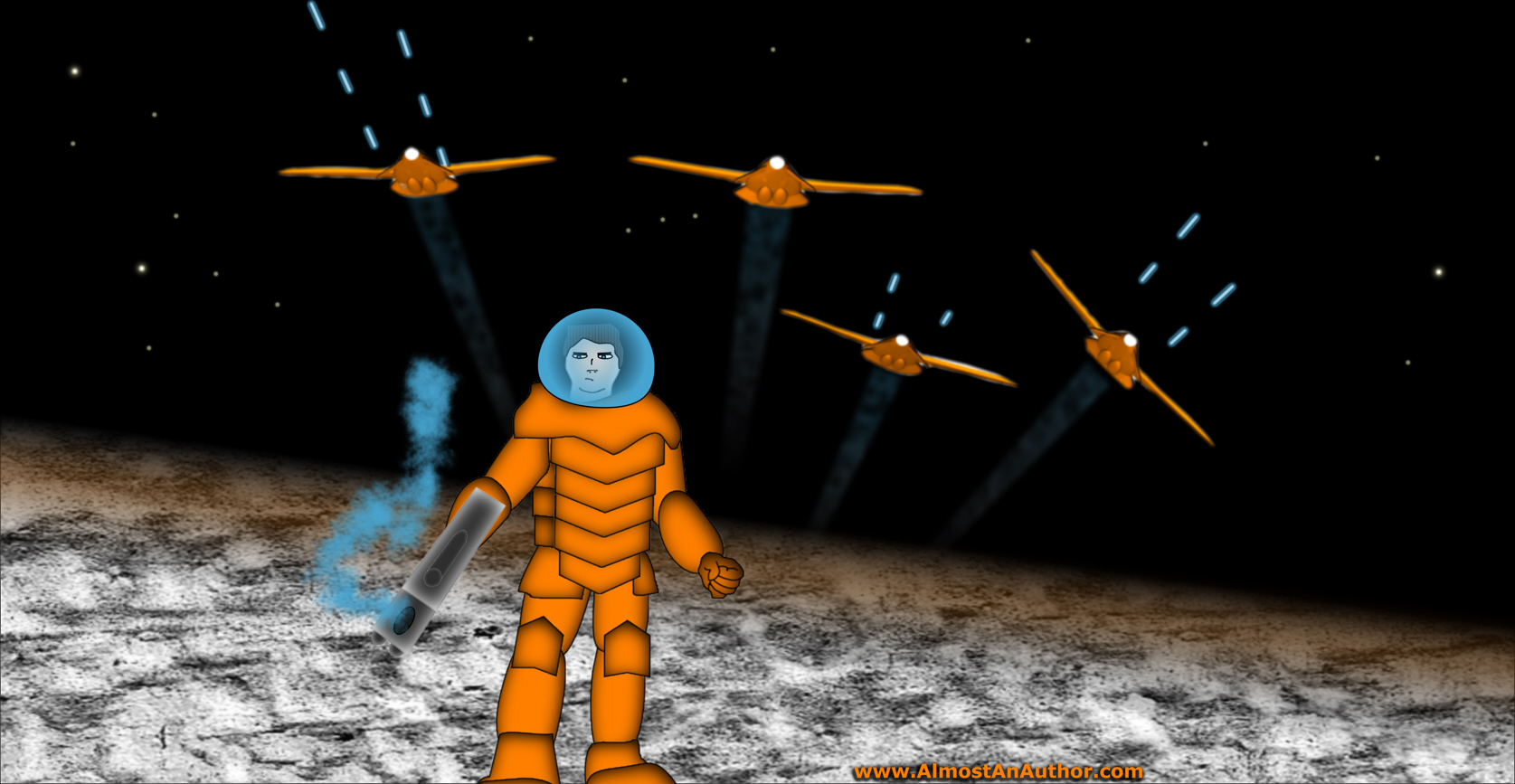

But can you use something weird like this in your storyworld? I can think of a few examples of similar creatures used in sci-fi settings. While the “Overlords” of Starcraft operate similar to jellyfish, they use air instead of water for their support. You might call them creatures with pneumostatic skeletons. I imagine they use a lighter-than-air gas (helium, hydrogen, etc.) to float around, but the game world never says. Similarly, the Hanar from Mass Effect are actually hydrostatic creatures that use anti-gravity fields to float around in the air. Jelly-type creatures are also a fairly common fantasy trope, but gelatinous cubes and such of D&D tend to operate more by magic than by any discernable physiology.

But can you use something weird like this in your storyworld? I can think of a few examples of similar creatures used in sci-fi settings. While the “Overlords” of Starcraft operate similar to jellyfish, they use air instead of water for their support. You might call them creatures with pneumostatic skeletons. I imagine they use a lighter-than-air gas (helium, hydrogen, etc.) to float around, but the game world never says. Similarly, the Hanar from Mass Effect are actually hydrostatic creatures that use anti-gravity fields to float around in the air. Jelly-type creatures are also a fairly common fantasy trope, but gelatinous cubes and such of D&D tend to operate more by magic than by any discernable physiology.

Non-skeletal creatures

Some creatures, such as worms, slugs, and octopuses, don’t have skeletons. While each of these animals moves in a slightly different way, they all rely on strong muscles to push against something and slide its body in that direction.

The iconic sandworm of Dune is one such example of a non-skeletal creature used in a storyworld for effect. A similar space-dwelling annelid is also seen in Empire Strikes Back. While there probably are intelligent annelids gastropods, and mollusks used in some books and movies, I’m not aware of any. These creatures tend to be the big scary monsters. Mindless, but terrifyingly so.

Parting thoughts

These are some ideas to get your creative juices flowing, but as an author you can create things not yet imagined. Perhaps an alien race of yours is bipedal but lacks any true bones the way we’d think of them. Or perhaps a creature is sustained and moves by some sort of force (evil or otherwise), like undead creatures in fantasy and horror novels. The important thing is to consider how a creature’s physiology adds or detracts from its functionality in your story. And then to exploit these benefits or penalties to the your story’s advantage.

Next month we’ll look at energy generation and use. Until then, let me know if you have any thoughts on alien or fantastic anatomy.

For much of the info in this topic, I am indebted to Life Science for Christian Schools, second edition, published in 1998 by Bob Jones University Press. And of course my lovely and talented wife, a medical doctor who thankfully paid more attention in high school biology class than I ever did.

Overlord Cartoon from: https://www.pinterest.com/julvalhe/starcraft/

We love helping your growing in your writing career.

We love helping your growing in your writing career.

No Comments